Unmasking Defence Evasion: .NET process injection

Over the past few days, I have been engrossed in researching various defence evasion techniques used by red team operators and APT groups. Specifically, I have been focused on finding methods to uncover the forensic artefacts left behind. This blog post will delve into the findings of my most recent endeavour: injecting processes with PowerShell and .NET assemblies to evade detection.

Fundementals

What is managed / unmanaged code? Managed code is code that is executed in a runtime. With .NET this runtime is CLR, or the Common Language Runtime. The managed code, in a bytecode format, is then loaded into the CLR which processes and executes the program.

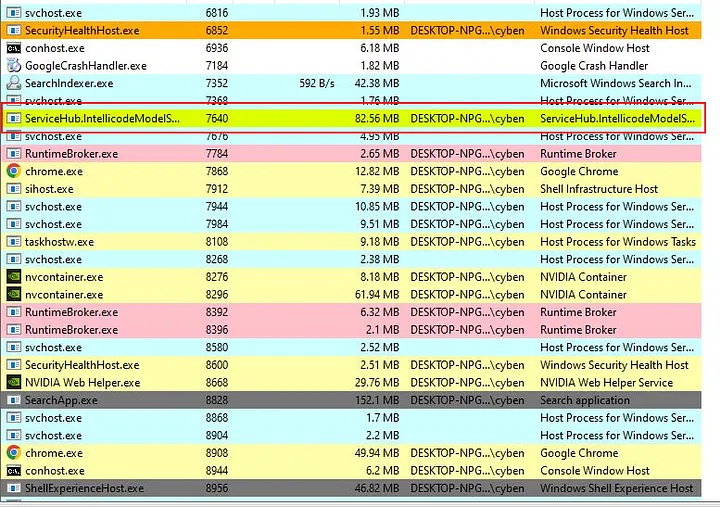

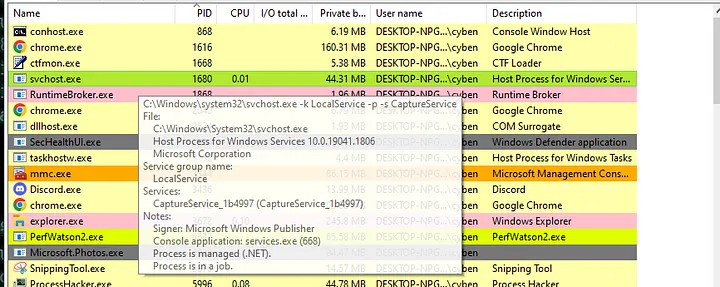

You can compare this to unmanaged code like C & C++ which are typically compiled and loaded into memory as a binary, which is then executed. We can use Process Hacker 2 to locate the managed processes, highlighted in green. All the other processes will be unmanaged.

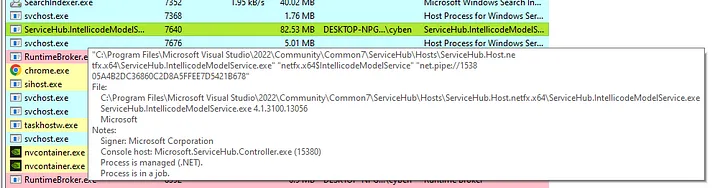

We can click & hover over this process to see more details.

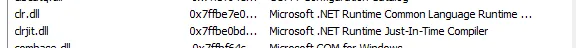

The above screenshot shows ‘Process is managed (.NET)’. Let’s have a look in more detail at the DLL loaded by this managed process.

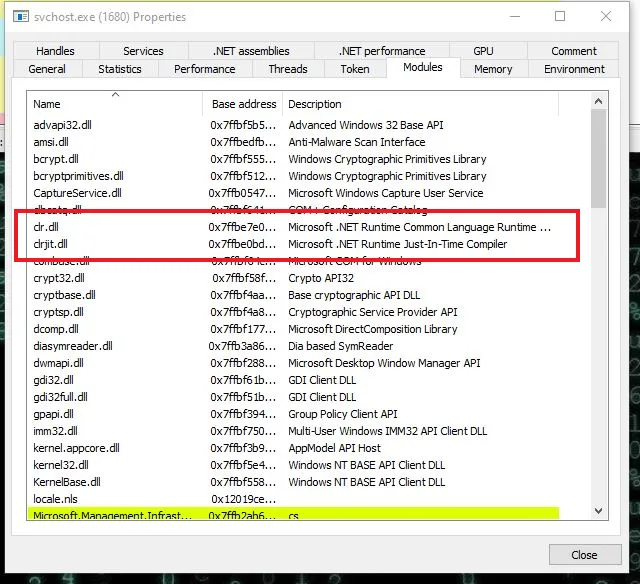

clr.dll and clrjit.dll are the two processes that are responsible for the .NET Common Language Runtime. All managed .NET processes will load these DLLs.

Injecting the CLR into unmanaged processes

Before I jump into this, let’s quickly go over why we should care and how this evades defences. Code executing from unmanaged Windows processes like svchost.exe , WmiPrvSE.exe , spoolsv.exe , chrome.exe ect ect, are less likely to be alerted by AVs or even EDRs as they are seen as ‘normal’ processes that will be running in a production environment. If we can inject a CLR, and the corresponding bytecode to be executed into the memory of any one of these processes we could possibly execute commands in-their-memory, without being detected as no files were ever dropped on the system. This technique of using another process to execute .NET assemblies was given the name Bring Your Own Land (BYOL) by Nathan Kirk from Mandiant

Cobalt Strike offers this post-exploitation capability with it’s execute-assembly feature, CLR runtime DLLs are loaded into an unmanaged processes memory along with malicious .NET assemblies to be executed. Cobalt Strike also has the powerpick command, this also loads a CLR into a unmanaged process and will execute a PowerShell command of the operators choice — without ever running from powershell.exe! As you will know, in Enterprise environments powershell.exe will often be restricted by application whitelisting, or monitored carefully, being able to run PowerShell commands in memory of an unmanaged process without powershell.exe ever being run becomes very powerful defence evasion mechanism.

Although I will not be demonstrating and analysing this Cobalt Strike command, the same DLLs will be loaded with both the execute-assembly and powerpick commands. Instead I will be using EmpireProject’s PSInject to inject PowerShell into an unmanaged process memory.

Before injecting, it’s important to note I am already running Sysmon with Event ID 7 ImageLoad enabled. This is one of the ways forensics artefacts can be gathered. Now let’s choose as process to inject.

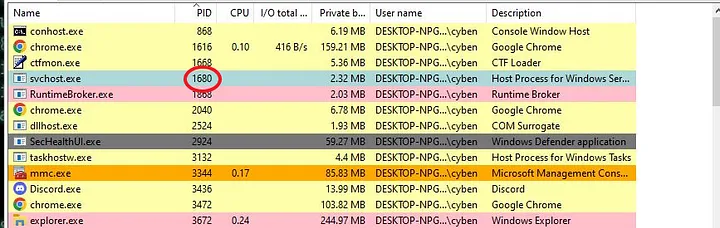

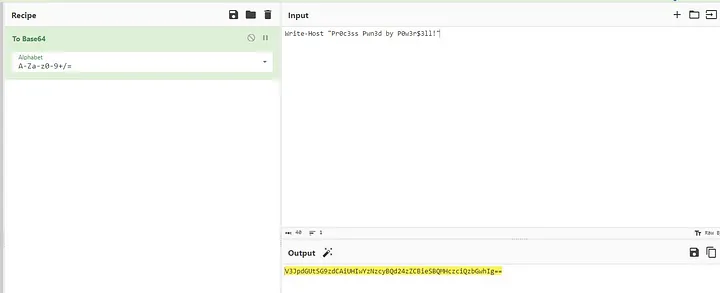

Let’s inject into PID 1680, svchost.exe. Let’s use the below command from the Invoke-PSInject script.

We supply the command to be executed with Base64 encoding.

After waiting a few seconds we can notice below that svchost.exe has changed colour. Hovering over it we can now see that this process has been injected and is now a managed .NET process.

Let’s dig deeper to confirm the DLL loaded into the memory of this process are as expected.

Nice, we have confirmation that the .NET CLR has been loaded into svchost.exe memory!

Detection with Sysmon

You will have noticed that yes I did use powershell.exe to inject the process with PowerShell in the first place (although the PowerShell is executing from svchost.exe, not powershell.exe), which would no-doubt flag detection and be logged, however with Cobalt Strike’s execute-assembly or powerpick , this would not be the case. Let’s assume I used the latter and I’ll now continue to search for forensic artefacts with sysmon logs, chainsaw & some custom Sigma rules I created!

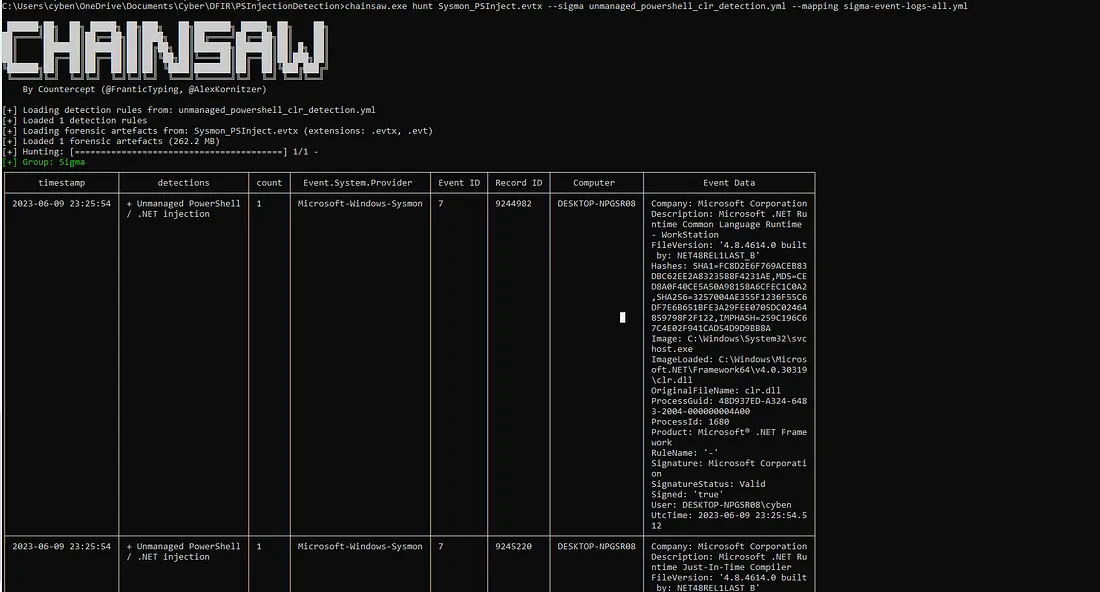

Sysmon Event ID 7, ImageLoad, logs when a DLL is loaded into a processes memory. Due the sheer quantity of these Event ID 7s with normal behaviour it’s unpractical to manually inspect each log, instead chainsaw and a Sigma ruleset will help extract what we are looking for. I couldn’t find any Sigma ruleset online that alerted DLL injection so I decided made my own. You can download it from here.

...

logsource:

product: windows

service: sysmon

detection:

selection:

EventID: 7

ImageLoaded:

- "*\\clr.dll"

- "*\\clrjit.dll"

filter:

EventID: 7

Image:

- "C:\\Windows\\System32\\WindowsPowerShell\\*"

- "C:\\Program Files\\Microsoft Visual Studio\\*"

- "C:\\Program Files (x86)\\Overwolf\\*"

- "C:\\Program Files (x86)\\Common Files\\Overwolf\\*"

condition: selection and not filter

falsepositives:

- Very possible. False postives will have to be added to filter list

level: high

These filters seemed to work on my machine, but I’m sure there will be false-positives that I didn’t experience in my testing. If in any of your experience with this Sigma rule that is the case, please PM me or comment on this the Image file path and I’ll update it.

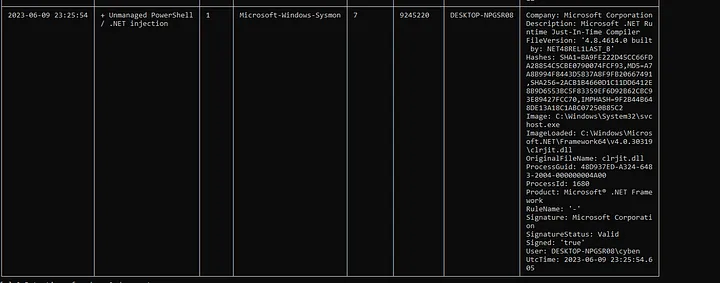

Using this Sigma ruleset with chainsaw we see the following the results.

e’ve got two detections from the Sigma rule, these detections are for clr.dll & clrjit.dll being loaded from svchost.exe on PID 1608, as expected. If you’ve discovered a forensic artefact of managed (.NET) process in an investigation, and your unsure if it should be managed, a quick way to confirm it’s legitimacy is by using the Sysinternal tool ListDLLs in a sandboxed Windows environment.

Nice! We’ve now found a way to carve out the evidence of unmanaged PowerShell process injection in the mass of logs. However, there is a few downsides to this method. Firstly, there is likely to be false positives, and secondly we don’t know what malicious code was actually executed, only that is has happened.

In my future blog posts, I’ll be explaining how we can counter this and actually start to unveil the contents of the loaded .NET assembly.